***This article is also available in Dutch***

Public space is an integral part of our daily lives. Every day we come into contact with a square, park, sidewalk, forest, playground, or shopping street. For example to move, to play, to move, to stroll, to meet, to sport or to rest. Depending on what we feel like. This freedom of choice in activities arises because these spaces are accessible to everyone. However, if you look a little further, you will see that certain places are often appropriated by certain people. This applies to adults, but certainly also to children. Several play areas are dominated by boys. Different studies show that occupational injustices arise in many play areas, because different children - especially girls - are restricted in their opportunities for play. This article is an overview of the relationships between boys and girls in public space. Based on an extensive literature review and own research we look at the causes of this gender inequality as well at the possible solutions.

Preface

Before we get into the subject a careful warning in advance: I’m aware - and research confirms this - that this dichotomy between boys and girls is somewhat precarious. Due to differences in for example age, competence, culture, education, personality, and position in the family there can be great differences between girls (and between boys). So, sex is by no means always the distinguishing factor. In addition, we shouldn’t be focusing on the biological dichotomy (males vs. females) but on gender (boyish and girlish or masculine and feminine behavior). Gender - just like childhood - is a social construct and is therefore accompanied by variation and change. However, for the sake of reading and for the purpose of this article, I write about the differences between boys and girls and take - with slight reluctance - the generalization and stereotyping that comes with it for granted. All for the sake of a higher purpose: to show that our public spaces are often designed for and used by certain type of persons and bodies.

|

| Girls and boys play together |

Past

In the 1960s and 1970s, there were still many families in cities with a large number of children. They often lived in a small house where they had to share the bedrooms. Those who wanted to avoid the crowds went outside or were sent outside if the parent(s) wanted a little more peace. More boys played outside than girls in those days, because girls were often constrained by domestic tasks and being entrusted with the younger family members at home (Ward, 1978; Hart, 1979). Another difference: while the boys could climb trees, get muddy in the pond and return home with their clothes torn, the girls were expected to return immaculate if they had been outside (Ward, 1978).

Girls were far less visible in the street. Some experts at that time related this to the fact that girls scored worse on tests about their visuo-spatial ability and that this is partly determined by a sex-linked recessive gene. An incorrect assumption. Research shows that it has more to do with learned behavior (nurture) than with hereditary traits (nature). The differences in spatial skills arose simply because boys were more outdoors and thus gained more environmental experience and confidence (Ward, 1978; Hart, 1979). They had every chance to explore and manipulate the public space. Boys were left much more free at that time, they went outside more often and further away. To play with friends but also to deliver newspapers, running errands or mowing lawns. The mean maximum distance boys were allowed to freely range away from their homes was more than twice that of the girls in both the younger and the older grades (Hart, 1979).

In the 1980s and 1990s we saw a significant decline in outdoor play among both boys and girls in North America and Europe. In addition to the fact that outdoor play was competing with increasingly more indoor options (larger bedrooms, more toys, computers, and more children’s programs on TV) there was a rising concern among parents about the safety of their children. Due to various incidents and media attention, concern among parents about children’s vulnerability to harassment, (sexual) assault, abduction and murder in public space increased (Valentine, 1996). The public space increasingly became a place against which children must be warned and protected (De Visscher, 2008). Besides these so-called ‘stranger dangers’ parents became also increasingly concerned that their children would come into contact with a rough and aggressively street culture that in some places was accompanied with underage drinking, drugs, vandalism and (petty) crime. In addition, due to the volume and speed of cars, there was already a fear of traffic accidents (Valentine, 1997).

As a consequence adults were and are controlling and restricting children’s use and experience of public space more and more often. Parents are increasingly opening up their homes to their children’s friends. They are also planning scheduled activities in private and safe areas in order to have more control over where their kids are and hence over their safety (Valentine, 1996; 1997; Skår & Krogh, 2009). It is striking and interesting for this article that two studies in the United Kingdom showed that the parents - with 8 to 11 year old children - did not distinguish between boys and girls. Parents perceived sons and daughters to be equally vulnerable in public space (Valentine, 1997; Brown et al., 2008).

Girls and younger children however report more fears for their personal safety in public space than boys and older children concerning ‘stranger danger’ or ‘fear of traffic’ (Valentine, 1997; Matthews, 2003). The social fear was certainly true for middle class urban and suburban girls. They spend more of their leisure time at home or in activities supervised by adults, so they had less local place knowledge and therefore less ‘escape routes’ when they were outside (Valentine, 1997).

|

| Fifteen boys (left) and five girls (right) play separately on a football field |

Present

The question is whether there are still differences between boys and girls when it comes to playing outside. Let's see some studies.

From 2007 through 2009, 1.450 U.S. households were interviewed by phone as part of the National Kids Survey about children’s time outdoors between the ages of 6 and 19 years (Larson et al, 2011). The percentage of boys spending two or more hours outdoors was higher than girls on both weekdays (68% vs. 57%) and weekends (81% vs. 75%). Girls were more likely than boys to spend less than one-half hour outdoors on both weekdays. If the years were compared, it turned out that girls displayed a slight decrease in time outdoors and boys a slight increase.

In Belgium a study was conducted in 1983, 2008 and 2019 in seven residential areas in and around the city of Antwerp (Meire, 2020). In 2008, girls were already slightly underrepresented at 45%, but in 2019 this had already fallen to 37% (a percentage equal to the 1983 results). There are however big differences in age. Among toddlers there is a balance between boys and girls. In the group of 6 to 8 years old 40% of the children playing outside are girls. But imbalance is particularly noticeable in the ages of 9 to 11 (only 27% girls) and from 12 to 14 years (34% girls).

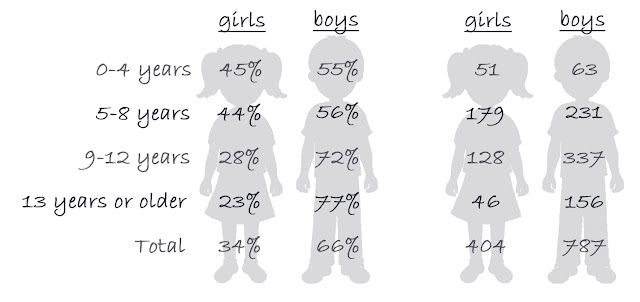

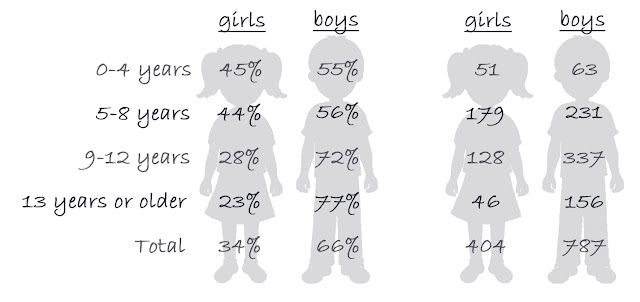

Last year I did a research in the Netherlands and we also encountered significantly more boys than girls (Helleman, 2021). Two-thirds of the children playing outside were boys and only one-third were girls. We also found big differences between the ages (Figure 1). In the younger age group - from zero to eight years - the ratio between boys and girls is almost equal. However, large differences arise with age. Girls aged nine years or older are playing less in public space than their male peers. Long-term user research in the Netherlands of children in public play spaces shows similar results (Vermeulen, 2017).

|

Figure 1. Who plays outside according to

gender and age (in percentages and numbers)? |

We also found in our research that girls were more 'supervised' than the boys (Helleman, 2021). And looking at the locations, we saw on average a nice equal distribution between boys and girls in the playgrounds (52%-48%) and in the bushes and shrubs (50%-50%), while the sports fields (92%) and lawns (82%) were dominated by boys. The most important activity for the girls were climbing, hanging or balancing. The second most important was 'doing nothing': relaxing, hanging out, sitting, watching or talking to other children. Boys were mainly engaged in ball sports.

Reasons

So there is still a significant difference between boys and girls when it comes to playing outside. Not only in the amount of time, but also where they play and what activities they engage in. What are the reasons for this? We saw in the past that this was largely due to the care tasks that girls had to perform. Although this still occurs in certain families and cultures (Lammers & Reith, 2011) this is - due to women's emancipation - a less explanatory factor. But then what? Based on an extensive literature study I describe three (interrelated) reasons: 1) girl’s preferences versus the design of public spaces; 2) boys, and 3) safety issues.

Reason 1: girl’s preferences versus the design of public spaces

Although there is no conclusive evidence, there are several studies (see box 1) that show that girls generally prefer more peaceful and social play activities and prefer to play in smaller groups. Boys prefer physically active and vigorous play, engaging in rough and tumble activities (chasing, rolling, wrestling) and in team play activities (soccer, basketball). Girls stay longer in playgrounds when there is a bigger variety of play equipment. This, of course, also applies to boys, but in general boys can also enjoy themselves with only a field and a ball.

It is still unclear how these differences arise. Why do girls play differently? Does it have to do with biological differences? Is it their own preference? Is it a consequence of parental interventions in their children’s engagement with sex-appropriate activities? And/or is it peer pressure among children to be socially accepted? Nevertheless, the outcome is that we see that boys are more concerned with sports-based, active leisure and space-consuming games, while girls play is more focused on social play.

Box 1 Girl’s preferences

Where, how and when children play outside largely depends on what they want, what they can and what they are allowed to do. Based on various studies, let's zoom in here on the different preferences of boys and girls.

A study in Germany at ten public playgrounds showed that boys were more likely to engage in sports and active games, while girls were more likely to be walking/running, to play on playground equipment, or be sedentary (Reimers et al., 2018). A study at an Australian primary school playground revealed similar things (Hyndman & Chancellor, 2015). Girls had a significantly higher enjoyment compared to boys for varied play consisting of symbolic/fantasy play, construction play, climbing, hiding, sliding, relaxing and tag games. They also play more with natural elements, while boys mainly use sports attributes.

A research with eleven teenage girls in Brisbane (Australia) found that parks were important settings for ‘social interaction’ when the girls were in early adolescence (11-14 years), but the parks were used more often as sites for ‘retreat’ in middle (15-17 years) and late (18 years and older) adolescence (Lloyd et al., 2008). This is in line with other studies showing that besides playing, girls especially like to socialize and chill out (Van Steijn, 2014; Vermeulen, 2017). Especially for adolescent girls passive recreation and relaxed leisure is important. In a research in two suburbs in and near London we see the same picture emerge. Besides ‘cycling around’ the interview data suggested that girls from 11 and 12 years old were mainly outside to see their friends or ‘watch the world go by’. Boys were more likely to have an interest in playing football, which was seldom shared by girls (Brown et al., 2008).

A research in 2003 in eight different playgrounds in multicultural Amsterdam neighborhoods showed that in each playground, boys outnumber girls (average of 66% vs. 33%). With increase of age, girls’ participation decreased even further. It also showed that most of the boys were playing soccer. They were playing in larger groups and using a larger area. Girls made clear that they are not attracted to playgrounds with very few play objects. Good quality and challenging play objects (high climbing frames, big swings) are a precondition to come out to play. It also showed that gendered activities were apparent in all playgrounds. Girls engaged in specific ‘girl’ activities with much variation in their daily play (gymnastics, hopscotch, playing on the swing). They tended to play much more with, at or inside the play objects than boys (Karsten, 2003).

Finally, twenty-four girls (8–10 years) in Sydney (Australia) were asked why they included certain features in their ideal school playground drawings. All participants identified at least two of the following themes: social interaction, physical activity, sensory experiences, freedom and/or skill mastery play. Girls sought out experiences that enabled them to test physical body limits, whilst maintaining a sense of control (Snow et al., 2019).

If we now look at the way in which the formal play areas are arranged, it is noticeable that it suits boys preferences more than those of girls. At certain spots we can actually speak of a boyish public space. After all, the public space is full of 1) protected and sterile play areas with a few fixed play elements and/or 2) open spaces with an even and hard surface (Dyment & O'Connell, 2013; Gill, 2021). The first offers opportunities to enrich gross-motor skills, but it often offers few opportunities for play that nurture the child's creativity, imagination, social interaction and co-operation (Fjeldsted, 1980; Hill, 1980). While that is precisely where the needs of girls lie. The second - open spaces - are also generally more suitable for and used by boys whose behavior is more wide-ranging. Girls rather play more clustered and have more intimate place-relationships. At these open spaces they are more relegated to the sidelines and on the fringes (Moore, 1980; Dyment & O'Connell, 2013; Spark et al., 2019; Snow et al., 2019; Miedema, 2020).

If you ask municipality officers what kind of places they provide for the older kids and youngsters you will probably hear that they have several football pitches and skate parks. Due to a lack of user research, impact measurements and evaluations they will not know that these facilities are used and dominated by boys. Research in Nottingham (England) and Australia found that skateparks for example were almost used entirely (90% and 95%) by males (Walker & Clark, 2020).

I did a little research at a nearby skate park/pump track and boys had the upper hand there too (first photo and photo below). On four different days I counted 82 participants, 67% of them where boys/men and 33% were girls/woman. Nearly 60% of the girls and the boys were active on a stunt scooter. A play attribute that seems to be much more gender neutral then a skateboard and also attracts a lot of children between the age of five and eight (50%).

|

| A skate park with fairly varied users |

Reason 2: Boys

Besides the mismatch between the girls preferences and the design of the play spaces there is something else that reinforces the inequality. Research shows that girls only play at places where they feel welcome and when a space is not claimed by other groups, such as boys or older teenagers. Especially the girls from nine years and older don't feel comfortable at what they call ‘boys places’. They are also less active when there are groups of boys present. In fact, girls don’t want to use those spaces and avoid them (Matthews, 2003; De Visscher, 2008; Reimers et al., 2018; Miedema, 2020; Walker & Clark, 2020).

Why don't girls go to places where boys are? Several mechanisms play a role here:

- First of all, some girls – especially from certain cultures – are not allowed to go to places where many boys come (Lammers & Reith, 2011);

- Secondly, as we saw before, boys tend to use larger spaces for their activities, so there is less room for girls and this also creates a sense of dominance. The boys have usurped the place. These conflicts of ownership are intensified when play space is limited and when there is a lack of diverse play opportunities (Korthals Altes, 2019);

- Third, girls are also left out because of rejection, bullying, and competitive behavior. The barrier to play outside is increased even further when boys are taunting and shaming the girls. Interviews with boys in the Amsterdam playgrounds confirm the gendered exclusion: “We cannot use girls. Girls do girl things and girls are stupid” (Karsten, 2003). In a study in Ghent (Belgium), several girls (10-12 years old) indicated that if they stop around a football field, they are usually called after, whistled or looked away by the boys (De Visscher, 2008). We also see this inappropriate behavior by boys and this form of active or passive protectionism in other studies (Lloyd et al., 2008; Lammers & Reith, 2011). At an inner city primary school in Melbourne (Australia) girls identified the football and soccer pitches as spaces that boys use and girls don’t (Spark et al., 2019). The girls described that they were not directly excluded, but indirectly through feelings of incompetence, a lack of control in organizing games, and through (un)conscious behavior of the boys in which they were establishing themselves as the ‘boss’.

Reason 3: Safety issues

Another reason for this difference between boys and girls was also current in 1978: "Boys can stay out longer and later. They, it is assumed, are more capable of looking after themselves. Parents fear for their girls" (Ward, 1978, p.132). Since then this protective parenting may have gotten even stronger. More and more children are receiving a sheltered upbringing. Parents are very protective for fear of strangers, harassment, traffic accidents and injury-risking behavior. Several studies show that those concerns are even more pronounced for girls than for boys (Boxberger & Reimers, 2019).

Due to these parental concerns children nowadays have limited independent mobility (i.e., freedom to travel to places and play outdoors without adult supervision) and therefore less opportunity to play outside (Reimers et al., 2018). It is good to know that in many cases there is no sharp dichotomy between boys and girls in terms of independent mobility. There are also cities where there are no such differences or only if there is a high degree of crime in a neighborhood (Miedema, 2020). Although there are also studies that contradict this violence hypothesis (Spilsbury, 2005). Gender plays a role, but not a singular role. The home-range is also influenced for example by age and culture. And the free range also differs per form of mobility (walking, cycling, public transport), the place of destination (parks, playground, local shops, sport facilities, shopping centre), and the number of friends (Valentine, 1997; Brown et al., 2008). Nevertheless, girls often seem to be less allowed to move freely.

Safety is an issue for their parents, but also for the girls themselves. From the age of eight years old girls feel ten times more insecure in public spaces then boys (Zimm, 2019). And this only increases with age. Plan International Belgium interviewed 359 girls (15-24 years) about sexual harassment in public space (Rombouts, 2021). 91% of them had already experienced this, varying from whistling, staring for a long time to unwanted touches. This male behavior also affects their freedom of movement. In another study, one in two girls indicated that they often take a detour, avoid certain places or no longer want to pass certain places alone.

Solutions

Outdoor play has many

advantages for kids (Helleman, 2018b). It gives them pleasure, it improves their health and it enriches different skills. Children who spend a lot of time outside and move independently can expand their environmental capabilities, in terms of their ability to understand and interact with their physical and social environment. They find their way about in it. An important condition for children to become citizens (Ward, 1978; Churchman, 2003). If girls also want to take advantage of these benefits, we have to fill in a few important things differently. I come to five solutions. In no particular order: 1) creating social safety, 2) raising attention to contemporary upbringing, 3) traffic safety measurements, 4) better design of public space, and 5) more dialogue.

Solution 1: creating social safety

Before we talk about quality, let's start with quantity: make sure there are enough play areas in a neighborhood, so that there are enough play spaces left for girls when guys take over certain spots. And the more there are, the closer they are to home. This provide an element of social safety that is particularly important in early adolescence for girls and their parents (Lloyd et al., 2008). After all, girls feel safe in spaces that are familiar and convenient (e.g., within walking distance of home).

Social safety issues also can be addressed by increasing the accessibility (i.e. making enough entrances), better lighting, good sightlines, making sure paths had no dead-ends and putting facilities for teenage girls in well-frequented areas (Walker, 2022). And by providing the needed maintenance: a neglected, dirty, and deserted space influences the feeling of insecurity. By tackling the visible signs of anti-social behavior and vandalism you prevent more serious crimes (see the so-called

broken window theory). And if necessary, appoint a concierge, steward, youth worker, usher, warden, park ranger or other person that can keep a watchful eye on the children. Or (preferable) organize enough eyes on and in the streets by creating places where many different people come (Jacobs, 1961). That creates a kind of informal social control, a self-policed space and therefore a feeling of safety.

The safety issue concerning the sexual harassment of teenagers goes far beyond the (re)design of public space. Major steps need to be taken in prevention, protection, participation and prosecution (Rombouts, 2021). Or as Colin Ward already said in 1978 (p. 136): “The problem of the girl in the city is a male problem”. So it is therefore especially important to broaden the focus: it shouldn’t be about protecting your daughter, but about educating your son. This can be done, for example, with promotional campaigns such as the campaign ‘

Have A Word With Yourself, Then With Your Mates’ from the London City Hall. Also in the city of Rotterdam (the Netherlands), efforts were made to raise public awareness with

campaigns and training professionals (Fischer & Vanderveen, 2022). In addition, the city developed the

StopApp in which perpetrators can be reported anonymously. The municipality also amended the local law so that perpetrators of street harassment could be fined, but the judge decided that whistling, cursing and yelling can’t be a criminal offense, because they are part of the freedom of speech...

Solution 2: raise attention to contemporary upbringing

Besides banning inappropriate and sexually transgressive behavior from boys, there is more work to be done in the field of upbringing. As shown before, parents have a major influence on the play behavior of their son and especially daughter. They determine the boundaries within children can fulfill their wishes and needs. They decide the freedom from kids within the residential area and in a certain play space when they are supervising. To create this awareness and reverse their course of action parents should be informed. Show them the benefits of playing outside and make them aware of the limitations they impose on their daughters. Also make them aware that there is a great distinction between the perception of insecurity and actual insecurity. Statistics show that there has never been so little crime in Western countries. Yet we have the opposite feeling because of the extensive media attention of incidents. Also striking: figures show that children are more likely to experience violence or abuse in ‘private spaces’ than in public spaces (Valentine, 1996). In other words, parents need to put certain things into perspective and be aware of what they withhold. Inform them how important it is that they give girls more rights to roam. And that they have more confidence in the skills of their daughters and give them the same or even more social support than boys. Encourage them and give permission to explore and use the public space.

Solution 3: traffic safety measurements

The journey is more important than the destination, is a much heard saying. This is especially true for kids. The journey itself is full of adventures and interesting sightseeing. However, when the journey is to challenging or unsafe for kids, then the destination is not reached. So, to encourage children’s active free play it is also important to consider their possibilities to travel unsupervised to play areas. It’s about the accessibility, but also about traffic and road safety. Although there are many

road safety measures (like speed humps, interconnected sidewalks, elevated crosswalks, protected lanes, temporary road closures, etc.) it is mostly about the prioritizing of walking and cycling in city planning. Taking the human scale and human speed as starting point. These measures logically have advantages for all genders and all ages, because they increase the radius of action of people and the accessibility of places. However, especially for girls - who are allowed to travel less far - this increases the chance of interesting play opportunities.

|

| Girls at a basket swing |

Solution 4: better design of public space

Fortunately there is an increasing awareness that planning and public space are mostly dominated by boys and often built for the ‘default male’ citizen (Walker & Clark, 2020). The answer to this problem is not to create separate places for boys and girls (divide). The philosophy of ‘gender mainstreaming’ is based on the idea that we should design inclusive public spaces that meet everyone’s needs and were everybody is feeling welcome (mix-up). Girls also find it nicer, more fun and safer if there is a diverse group of people in terms of age and gender.

There are several important

factors for realizing play-friendly cities, such as attractiveness, challenging, comfort, diversity, inviting, and livability (Helleman, 2018a). Conditions that apply to all children. However, there are a number of factors that are of extra importance to girls. Based on research and literature (Moore, 1980; Karsten, 2003; Brown et al., 2008; Lloyd et al., 2008; Dyment & O’Connell, 2013; Van Steijn, 2014; Rubin & Ågren, 2016; Helleman, 2018a; Reimers et al., 2018; Korthals Altes, 2019; Snow et al., 2019; Spark et al., 2019; Zimm, 2019; Miedema, 2020; Walker & Clark, 2020; Kocmaruk, 2021) I name a number:

- Make play areas big enough to facilitate play by both boys and girls. That means that the terrain for play equipment (such as slides, bars, swings, climbing structures, sand boxes, water places) should take up as much territory as the area for ball games.

- Think less in large, mono-functional play areas. Smaller places at one play space prevent girls becoming marginalized as happens in big open spaces. So, differentiate and create more defined places in a play space with different play types and play activities for all generations and for people with different skills.

- Besides playing, girls especially like to chill out. Create places and attributes where you can sit together face to face, hang out, socialize and chat are loved by many girls. That’s why a basket swing or hammock is chosen must often by girls as a place to play, sit, meet and chill.

- Girls stay longer in play areas when there is a bigger variety of play opportunities. Therefore, provide a varied play area that is diverse in color, height, surface, materials, features, activities, and attributes. This offers possibilities for play as well as viewing, seating, and chatting options.

- Loose parts, including natural materials (sticks, branches, leaves, stones), moldable materials (sand, clay, chalk, water), and man-made objects without obvious play purpose (tyres, crates, ropes) provide opportunities to explore and engage in imaginative and constructive play, which girls like.

- Another way to stimulate imagination and creativity, is by making places for dancing, moving and (making) music.

- Add and make natural elements (such as trees, bushes and water) accessible and playable. Nature often makes gender differences smaller. And perhaps even more than boys, girls are looking for adventure and places to experience, explore, investigate and use spaces for their own purposes (adaptability).

- Connect to more gender-neutral forms of play, such as climbing and building. But also in terms of sports: so rather a skate park with skate ramps and hills of different heights suitable for roller skates, stunt scooters, bicycles and skateboards than a few very high half pipes that mainly attract male skateboarders.

Solution 5: more dialogue

Finally, part of the solution also involves organizing participation. The (re)design of play spaces is mostly handled by the municipality, a landscape architect or an employee of a playground equipment factory. The opinion of its potential users is rarely asked. If an opinion is asked, it is often from the parents. So, most of the time children are not consulted about their wishes (Moore-Cherry et al., 2019; Snow et al., 2019; Walker, 2022). And when a play space is completed, it is rarely investigated whether and how it is used and by whom (and who is missing).

The famous urbanist Jane Jabobs (1961) already said: “Cities have the capability of providing something for everybody, only because, and only when, they are created by everybody.” To incorporate the wishes and needs of children - and girls in particular - it is necessary that they will get a serious role in the planning and design process. Not only for play spaces, but for the city as a whole. Because a more inclusive process results in a more equal and multifaceted urban environment (Moore-Cherry et al., 2019; Zimm, 2019). That means really giving time and space for input. This can be done in multiple ways: by observing their real behavior when they are playing, to walk along with children, by asking them to make photos of barriers and play spaces, by organizing design and dialogue sessions, etc. How you do it isn't even that important, as long as you do it seriously. And that applies to all the above points if you want to work on equality and equity in public space.

Photos by (c) Gerben Helleman

Was this article helpful? Or do you have additions or tips? Let me know in a comment below.

Literature and notes for further reading

Brown, B., Mackettb, R., Gong, Y., Kitazawac, K. & Paskins, J. (2008). Gender differences in children’s pathways to independent mobility. In: Children's Geographies, 6 (4), pp. 385-401.

Boxberger, K. & Reimers, A.K. (2019). Parental correlates of outdoor play in boys and girls aged 0 to 12 - a systematic review. In: International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16, pp.1-19.

Churchman, A. (2003). Is There a Place for Children in the City? In: Journal of Urban Design, 8 (2), pp. 99-111.

Drift, M. van der (2021, 1 juli). Van Wie is de Straat? II - De emancipatie van de publieke ruimte [aflevering Focus]. Hilversum, Nederland: NPO radio 1.

Dyment, J. & O'Connell, T. S. (2013). The impact of playground design on play choices and behaviors of pre-school children. In: Children's Geographies, 11 (3), pp. 263-280.

Erden, F.T. & Alpaslan, Z.G. (2017). Gender Issues in Outdoor Play. In: Waller, T. et al. (eds.) The SAGE Handbook of Outdoor Play and Learning (pp. 348-361). London: SAGE Publications.

Fischer, T. & Vanderveen, G. (2022). Seksuele straatintimidatie in Rotterdam onverminderd groot probleem. Website Sociale Vraagstukken.

Fjeldsted, B. (1980) 'Standard' versus 'adventure' playground. In: Wilkinson, P.F. (eds.) Innovation in play environments (pp. 34-44). London: Croom Helm.

Gill, T. (2021). Urban playground: how child-friendly planning and design can save cities. London: RIBA Publishing.

Hart, R. (1978). Children's Experience of Place. New York: Irvington Publishers.

Hill, P. (1980) Toward the perfect play experience. In: Wilkinson, P.F. (eds.) Innovation in play environments (pp. 23-33). London: Croom Helm.

Hyndman, B. & Chancellor, B. (2015). Engaging children in activities beyond the classroom walls: A social–ecological exploration of Australian primary school children’s enjoyment of school play activities. In: Journal of Playwork Practice, 2 (2), pp. 117–141.

Jacobs, J. (1961). The Death and Life of Great American Cities. Random House Usa Inc.

Karsten, L. (2003). Children’s Use of Public Space. In: Childhood, 10 (4), pp. 457-473.

Kocmaruk, J. (2021). Measuring Park Quality for Youth 13-19. Langara Applied Planning Program Major Project.

Korthals Altes, R. (2019). Creating spatial justice from the start: at the child’s level. In: Bester, M., Sempere, R.M. & Kahne, J. (eds.) Our city? Countering exclusion in public space (pp. 277-285). Rotterdam: STIPO.

Lammers, D. & Reith, W. (2011). Jong spreekt Jong: het leven van jongeren in de Schilderswijk. Den Haag: De Haagse Hogeschool.

Larson, L.R., Green, G.T. & Cordell, H.K. (2011). Children’s Time Outdoors Results and Implications of the National Kids Survey. In: Journal of Park and Recreation Administration, 29 (1), pp. 1-20.

Lloyd, K., Burden J., & Kiewa, J. (2008). Young Girls and Urban Parks: Planning for Transition Through Adolescence. In: Journal of Park and Recreation Administration, 26 (3), pp. 21-38.

Matthews, H. (2003). The street as a liminal space: the barbed spaces of childhood. In: Christensen, P. & O’Brien, M. (eds.) Children in the City: home, neighbourhood and community (pp. 101-117). London/New York: RoutlegdeFalmer.

Moore, R.C. (1980). Generating relevant urban childhood places: learning from the ‘yard’. In: Wilkinson, P.F. (eds.) Innovation in play environments (pp. 45-75). London: Croom Helm.

Moore-Cherry, N., Copeland, A., Denker, M., Murphy, N. & Bhriain, N. (2019). The playful city: A tool to develop more inclusive, safe and vibrant intergenerational urban communities. In: Bester, M., Sempere, R.M. & Kahne, J. (eds.) Our city? Countering exclusion in public space (pp. 269-275 ). Rotterdam: STIPO.

Reimers, A.K., Schoeppe, S., Demetriou, Y., & Knapp, G. (2018). Physical Activity and Outdoor Play of Children in Public Playgrounds - Do Gender and Social Environment Matter? In: International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15 (7), pp. 1-14.

Rombouts, H. (2021). Safer Cities: voor veilige en inclusieve steden in Antwerpen, Brussel en Charleroi. Brussel: Plan International België.

Rubin, R. & Ågren, A. (2016). Flickrum – Places for girls. White Arkitekter.

Skår, M. & Krogh, E. (2009). Changes in children’s nature-based experiences near home: from spontaneous play to adult-controlled, planned and organized activities. In: Children's Geographies, 7 (3), pp. 339-354.

Snow, D., Bundy, A., Tranter, P., Wyver S., Naughton, G., Ragen, J. & Engelen, L. (2019). Girls’ perspectives on the ideal school playground experience: an exploratory study of four Australian primary schools. In: Children's Geographies, 17 (2), pp. 148-161.

Spark, C., Porter, L. & Kleyn, L. de (2019). ‘We’re not very good at soccer’: gender, space and competence in a Victorian primary school. In: Children's Geographies, 17 (2), pp. 190-203.

Spilsbury, J.C. (2005). ‘We don’t really get to go out in the front yard’—Children’s Home Range and Neighborhood Violence. In: Children's Geographies, 3 (1), pp. 79-99.

Steijn, A., van (2014) ‘Vrouwen en meiden laatst’. Tilburg: Goede Speelprojecten.

Meire, J. (2020). Het grote buitenspeelonderzoek: buiten spelen in de buurt geobserveerd. Kind & Samenleving.

Valentine, G. (1996). Children should be seen and not heard: the production and transgression of adult’s public space. In: Urban Geography, 17 (3), pp. 205-220.

Valentine, G. (1997). “Oh yes I can.” “Oh no you can’t”: children and parents’ understandings of kids’ competence to negotiate public space safely. In: Antipode, 29 (1), pp. 65-89.

Vermeulen, D. (2017) Gender en buitenspelen op openbare speelplekken. Utrecht: Speelforum.

Visscher, S. De (2008). De sociaal-pedagogische betekenis van de woonomgeving. Gent: Universiteit Gent.

Walker, S. (2022). Make Space for Girls. In: Landscape, 1, pp. 25-27

Waller, T., Ärlemalm-Hagsér, E., Sandseter, E. B. H., Lee-Hammond, L., Lekies, K., & Wyver, S. (2017). Introduction. In: Waller, T. et al. (eds.) The SAGE Handbook of Outdoor Play and Learning (pp. 1-21). London: SAGE Publications.

Ward, C. (1978). The Child in the City. Architectural Press.

Zimm, M. (2019). Girls’ room in public space; planning for equity with a girl’s perspective. In: Bester, M., Sempere, R.M. & Kahne, J. (eds.) Our city? Countering exclusion in public space (pp. 167-171). Rotterdam: STIPO.

Everybody, read this. It is such a brilliant - and damning - overview of the way we build parks now.

ReplyDeleteEssential reading for parents, educators and urban planners....a really excellent article explaining how we got here and what we can do about it.

ReplyDeleteExcellent!

ReplyDeleteHow do we design public play places that are rich in "opportunities for play that nurture the child's creativity, imagination, social interaction and co-operation"? Sign me up for helping implement all of the solutions discussed here!

ReplyDeleteThank you for this excellent article

ReplyDeleteThis is such a thoughtfully written article outlining some fascinating research which gets to the heart of how to increase equity in girls' access to #outdoorplay. Well worth the read!

ReplyDeleteExcellent read

ReplyDeleteA thorough review of differences in girl's & boy's outdoor play with 5 practical solutions for supporting girl's time outdoors.

ReplyDeleteA really interesting read!

ReplyDeleteA fantastic piece and looking forward to doing this work in the US somehow!

ReplyDeleteInteresting work! Congrats. We are engaging feminist geog theories in understanding the gendered presence in public space (and especially on streets) and finding similar results.

ReplyDeleteDid you also contact 'Woman skate the world'? They can add great insights to your research.

ReplyDeleteThis is a fascinating article: it definitely mirrows my experience as a child and that of my daughter and her friends. I do hope placemakers take note when creating play areas.

ReplyDeleteA really clear articulation of the issues with many existing public play spaces and how better design and socialisation can support and even empower girls to have quality participation in public life.

ReplyDeleteBrilliant article - access to nature, play and public space isn't equal, in fact it's far from it. There is so much we can do to shift the narrative, and to start to make charge.

ReplyDeleteReally great article with so much to draw from it.

ReplyDeleteWow, this. Heartbreaking to see in the included tables the significant disappearance of girls from public spaces as they become young women. I remember that. I remember my already limited access disappearing the minute I got breasts.

ReplyDeleteHaving gone to an all girls' school and not having a brother I never understood the dominance of space by boys and men (like golf courses!). Let's ensure that both our boy and girl children can thrive equally.

ReplyDeleteSome great insights. So often we move to building the next playground or skatepark, before truly understanding how inclusive these facilities actually are.

ReplyDeleteAnecdotal: my mother roamed far & wide as a kid; basically it was casual fell running. She also seemed to conduct her entire academic & professional career as if she'd never got the memo it was supposed to be more difficult for women. I always thought both sprung merely from personality, but looking at this, the former probably nurtured & increased the latter possibility re work.

ReplyDelete